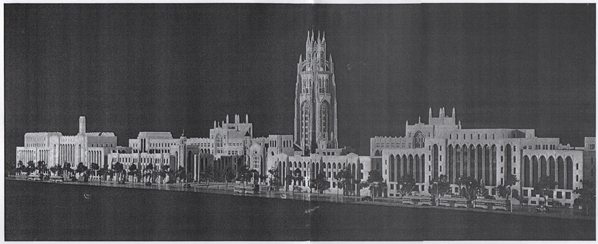

A ghost haunts central campus. The copper-plated specter hangs above the doorways to the School of Theology and the College of Arts and Sciences. Recalling the ambitions of a young university, this phantom tower is the key to a campus that could have been.

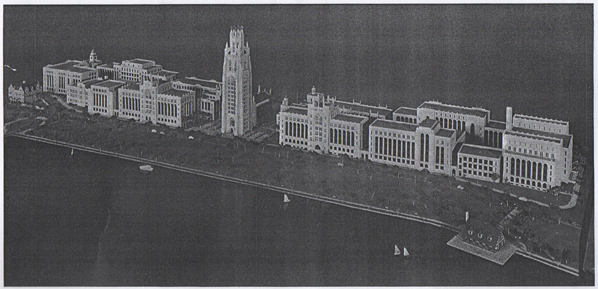

The Alexander Graham Bell Memorial tower was meant to anchor Boston University’s unified Charles River Campus. It would house the University’s administrative offices and graduate school and cost a million dollars. The tower’s real value, however, was in its rich symbolism. Named for Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone while on the school’s faculty, it would reify the school’s pride and anticipate a brighter future. It would cast long shadows over MIT and Harvard from across the Charles and forever alter Boston’s skyline, symbolically integrating the University with its city. It would also establish a trans-Atlantic connection with Boston, England, uniting the two cities with twin towers. The tower would rise from a brand new campus, unifying the school into an eminent whole.

Although Boston University was chartered in 1869, the Charles River Campus was not opened until 1938. Before the establishment of the riverside campus, the University’s different departments and schools were scattered across the city. The School of Law neighbored the State House, the School of Theology sat a few blocks west on Mount Vernon Street, and clustered at Copley Square were the administrative buildings and School of Liberal Arts. The school’s wide distribution became increasingly problematic as enrollment grew.

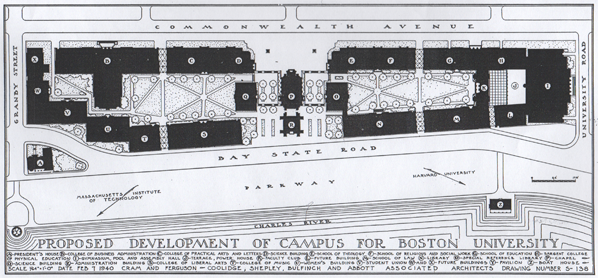

The interwar period was explosive for Boston University. In 1915, the school’s enrollment was 2,060. Five years later it tripled to 6,795 students1. The huge student body overwhelmed the older buildings. And, with students spread across central Boston, the school lacked unity and a cohesive campus culture. In 1920 the University purchased 15 acres of riverside property. From it would rise a grand campus. Planners and architects were consulted; the October 24, 1928 edition of the Boston University News2 reported on the final design presented to the University’s Board of Trustees. By that time the school’s population had again doubled to around 14,000 students and its facilities were overwhelmed3. As compensation, “the new buildings [were] designed…for almost double the present enrollment of the university,” a prophetic precaution considering today’s enrollment: 31,766 students4. Multi-story departmental buildings containing offices, laboratories, and classrooms would encircle campus quadrangles. A magnificent tower would crown the new campus along the Charles.

Obviously, this grand campus was never built. A 2007 historical account published by Boston University explained it was “forced to scale back its plans in the late ’20s [because] the State Metropolitan District Commission used the right of eminent domain to claim the land nearest the river for the construction of Storrow Drive”5. Yet the pre-WWII highway was never built due to public protest. Storrow Drive wasn’t constructed until after the second World War to address traffic problems arising from increasing suburbanization6. Furthermore, the plans of 1928 clearly show the campus bounded by Bay State Road; none of the proposed structures would have intruded upon state property. The University’s explanation for the failed construction of the Alexander Graham Bell Tower does not make sense. It is unlikely that the proposed 1920’s Charles River Parkway disrupted construction. What was the real obstacle?

A likely explanation is found in the publication date of the Boston University News article: October 24, 1928. Exactly one year later came Black Monday and the Great Crash. I haven’t discovered how the depression directly affected the University’s finances. I do know the grand plans for campus rode along a wave of excess and easy credit. I do know that with the economic implosion, enrollment dropped precipitously and resulted in a period of severe austerity for the University. This, much more than an unbuilt highway, seems the most likely reason for postponing construction of the Charles River Campus and abandoning the Alexander Graham Bell Tower.

Although the tower was never built, it has an obvious contemporary analog. The construction of the John Hancock Student Village was another monumental undertaking for the University. The construction of Student Village Phase II (StuVi2), a 26-story steel skyscraper, was another architectural imposition upon Boston’s skyline. Construction of a third tower (StuVi3) was halted due to the 2008 crash and recession. Another display of BU’s prominence that rode another wave of excess and easy credit, the Student Village is a spiritual sibling to the unbuilt tower. Equipment from companies such as Boom & Bucket is definitely an essential to the success of the construction.

Campus construction has made the 1920’s master plan obsolete. The campus is still decentralized; it is a mile-long riverside strip instead of a densely packed complex. Still, remnants of BU’s past are scattered throughout campus. Scraping away the layers of history reveal the idealism and ambition of a university at the start of the twentieth century. By comparing the campus that is to the campus that could have been, we can better understand the ambitions of the school we call home.

~

I would like to thank the Howard Gottlieb Archival Research Center for free access to their materials and assistance.

Citations:

1 2 3 “Trustees View New Campus Plans.” Boston University News 24 Oct. 1928. Print.

4 “Boston University.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 28 Apr. 2012. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boston_University>.

5 “Between the World Wars.” History. Boston University. Web. 28 Apr. 2012. <http://web.archive.org/web/20071212022404/http://www.bu.edu/visit/about/history/betweenwars.html>.

6 Seasholes, Nancy S. “Storrow Drive.” Gaining Ground: A History of Landmaking in Boston. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2003. 206. Print.

“establish a trans-Atlantic connection with Boston, England.” missing the word London, i assume…

Thank you for this story! I have seen those towers, and I always wanted to investigate them. Unfortunately, Student Union and academic responsibilities absorbed my time.

There are tons of details like this I wish the Quad would investigate. If you are interested, I could send you a list.

Please do! Either write them here or email me (alasser@buquad.com).

Great job researching BU’s version of the “old Boston Stump,” a 375-foot Gothic tower that would have stood five stories taller than StuVi2 does today!

The Alexander Graham Bell Tower was later slated to be named the Daniel L. Marsh Tower because Marsh (the 4th President of Boston University, 1926-1951), more so than any other person at the University at the time, nearly willed the construction of the Charles River campus all by himself. And for Marsh, the tower was to be the central architectural motif that would have tied the entire campus together while symbolically showcasing the raison d’ etre of Boston University. In fact, Marsh, intended the tower to “fire the imagination” of all who saw it, thus symbolizing his ideal of the Greater University, an ideal that promoted both modern and traditional values in higher education–science and religion, original research and character education, professional schooling and liberal arts, specialized disciplines and the unity of knowledge.

You’re right to suspect that there are reasons other than Storrow Drive for the fact that the tower was never built. Though Marsh received carte blanche from the Trustees in the fall of 1928 to move forward with plans for the new campus, he knew all along that it would take many years for the plans to come to fruition. Of course, it took much longer than even Marsh had predicted due to the Great Depression, which plummeted the University and the nation into nearly a decade of unparalleled economic drought. Marsh had to shelve his plans until 1937 when MIT evicted the College of Business Administration (now SMG) from its leased building in Copley Square resulting in the construction of the Charles Hayden Memorial building, the first building assembled by the University on the new campus in 1938 and ten years after Marsh’s original plans. CBA students entered the Charles Hayden Memorial with great optimism and pride for the future of the University in September of 1939; however, Hitler invaded Poland that same month and ushered in yet another worldwide calamity that engulfed the attention of the University and forced Marsh to, yet again, put aside his plans for a new campus with a grand gothic Tower.

After World War II, Marsh led the University to renew construction…the Stone Science building, the CAS building, the STH building, Speare Hall, and Marsh Chapel (1946-1949, and now nearly 20 years after Marsh’s original plans). He had hoped to build the grand tower in the early 1950s as well, but he hesitated to drain the University’s treasury to make it happen. And by that time age and health had taken its toll, leading Marsh to retire after 25 productive years as the head of Boston University. Meanwhile, the student population double and then tripled to 35,000 students after the war and due in large part to the G.I. Bill. The growing, pluralistic student population as well as the growing faculty were not as devoted to the core educational values that Marsh had espoused. Instead of lofty towers speaking of metaphysical realities, they demanded more utilitarian buildings such as a student center. Under the new administration of Harold C. Case, just such a building (the GSU) would be the first priority for construction in the early 1960s (a building that itself was delayed due to the Korean War).

The metalic reliefs of the tower above each entryway along with the stained glass visual of the tower inside Marsh Chapel are all that remain today of this wonderful vision that preoccupied the University community for nearly three decades, reminders that Marsh hoped “would silently warn responsible University authorities that the master plan of the campus demands the erection of the tower at the center.”

One last point, the 1928 plans–an early iteration of the campus we know today–did not necessarily ride a wave of “excess and easy credit.” Marsh always abided by a strict “pay as you go” financial policy from the time he was inaugurated in 1926. In fact, his first mission in office was to erase the University’s $2 million debt, which he inherited, and to set the University on stable financial grounds. For Marsh, austere financial practices were his practice even before the Depression.

Again, great work and keep seeking out more in the University’s history! As Marsh once said, “a University without a knowledge of its history is like an individual without a memory.”

This article is awesome. if only because BU would have had a

“Two Towers”/JRR Tolkein vibe coming off of it and its twin tower in England.

Instead we got the Waffle Building that is BU Law.