In an effort to personalize the potential impacts of climate change, the White House unveiled a new website last week that compiles data about future environmental risks like coastal flooding, sea level rise, and eventually drought as well as the risks of extreme weather events.

The hope is that researchers and developers will take the data and create apps and visualizations in order to localize the effects of climate change making them digestible, a press release accompanying the announcement of the site explained.

Already, the New York Times reported that Google is thinking about how to increase the user-friendliness of data on sea level rise and drought in a program much like Google Earth, albeit not quite as simple.

A few government organizations are also holding challenges to encourage people to get creative and use the data. NASA announced the first of such challenges just a few days after the new site went live.

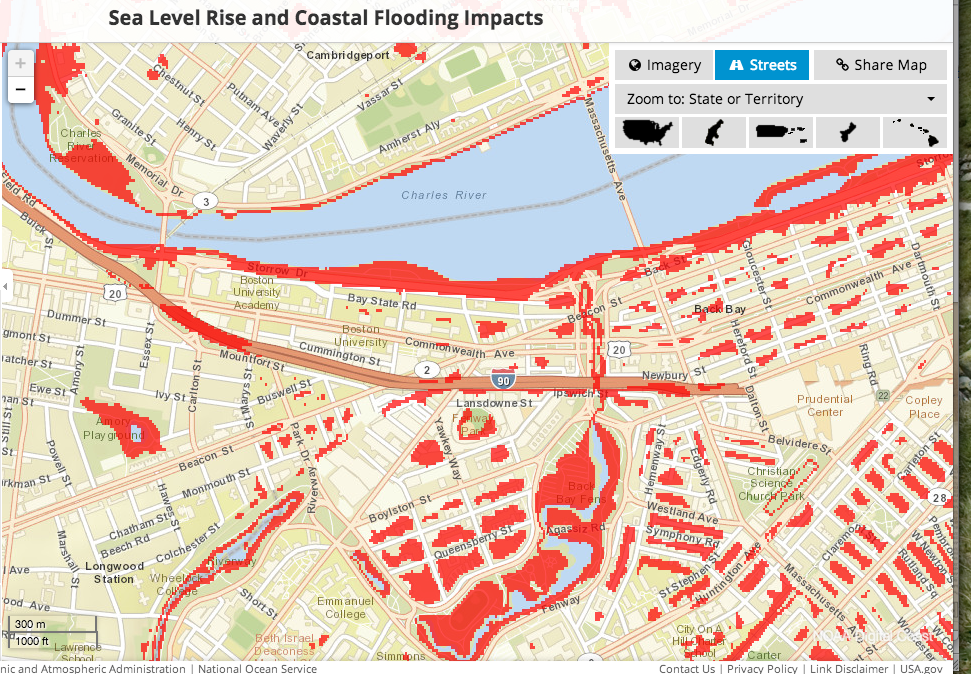

It calls on people to use data from NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to create visualizations of the risk homes and businesses face from coastal flooding.

In Boston, city officials see a lot of promise in the site and what will come out of it.

“There’s a lot to be said for making climate change impacts clear on a local scale,” said Charles Zhu, who managed the Greenovate Boston Initiative and was in Washington for the White House’s announcement of the website.

“With this data—and the accompanying apps and visualizations and maps—my hope is people will be able to click on a map and see how much of their house is underwater,” or how prone they are to other impacts of climate change, he said.

James Baldwin, visiting assistant professor in BU’s department of earth and environment, wrote in an email that he hopes the new website will help inform the public about climate change.

“There is a substantial disconnect between the scientific communities understanding of climate change and the public’s. Hopefully putting this data out there will help bridge that gap,” he wrote.

Baldwin added that, while scientists already have access to the data that is now available to the public, the site compiles that data in one place and makes it easy to use, which benefits other people doing research like students, planners and businesses.

Boston city officials are happy to have a more coherent and reliable source of climate change data than before when data was scattered across different agencies and it wasn’t always clear what was good and what was not.

Zhu said having such specific data is helpful in identifying what parts of the city are most at risk in the event of catastrophic flooding and how best to help them.

Still, Rick Reibstein, adjunct professor of environmental law and policy in the College of Arts and Sciences, stressed that focusing on how to adapt to the impacts of climate change only addresses the symptoms, leaving the root of the problem untouched.

“We have a history of addressing environmental problems piece by piece and inefficiently,” he said, adding that climate change has proved to be no different.

While data on sea level rise and coastal flooding can help a city like Boston better prepare for catastrophic flooding, it will not fix the larger problem—the burning of earth-warming fossil fuels.

“We are never going to solve this problem unless we have a new set of incentives and disincentives to leave [fossil fuels] in the ground,” Reibstein said.

Reibstein said he appreciates the value of educating the public about the effects of global warming in attempts to prevent it. But he explained, those in the public who research and advocate about the issue are going up against powerful business interests.

No matter how educated the public is about the effects of climate change, he said without the necessary support, its interests are liable to get overshadowed by those who can afford to participate in the political process.

“It’s not enough to just tell the public what they need to know and expect the politics to happen,” Reibstein said. “You need a lot more than that.”