The Joy of Writing

By Wislawa Szymborska

Why does this written doe bound through these written woods?

For a drink of written water from a spring

whose surface will xerox her soft muzzle?

Why does she lift her head; does she hear something?

Perched on four slim legs borrowed from the truth,

she pricks up her ears beneath my fingertips.

Silence – this word also rustles across the page

and parts the boughs

that have sprouted from the word “woods.”

Lying in wait, set to pounce on the blank page,

are letters up to no good,

clutches of clauses so subordinate

they’ll never let her get away.

Each drop of ink contains a fair supply

of hunters, equipped with squinting eyes behind their sights,

prepared to swarm the sloping pen at any moment,

surround the doe, and slowly aim their guns.

They forget that what’s here isn’t life.

Other laws, black on white, obtain.

The twinkling of an eye will take as long as I say,

and will, if I wish, divide into tiny eternities,

full of bullets stopped in mid-flight.

Not a thing will ever happen unless I say so.

Without my blessing, not a leaf will fall,

not a blade of grass will bend beneath that little hoof’s full stop.

Is there then a world

where I rule absolutely on fate?

A time I bind with chains of signs?

An existence become endless at my bidding?

The joy of writing.

The power of preserving.

Revenge of a mortal hand.

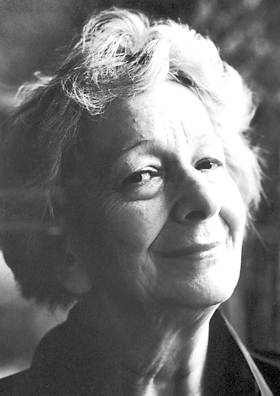

This poem, in which Szymborska discusses the power, beauty and joy of the written word and poetry, helped the Polish poet to win the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature.

In the poem, the speaker speaks of writing about a “written doe” that is bound by “written woods.” This doe may be bound to the woods, but it is not bound to the dimensions of the paper.

The speaker uses the imagery of, “she pricks up her ears beneath my fingertips.” This eight-word line gives the reader, or at least me, the vision of an imaginary doe that instantly becomes alive as the writer puts pen to paper and marks the letters D, O, E. It gives the vision that the doe only exists because the writer has created it. And yet this doe is able to come to life because the writer has created it.

The poem ends with the lines, “The power of preserving/ Revenge of a mortal hand.” The speaker suggests that not only does poetry give the writer a chance to create, but also the chance to preserve. In the “real world,” we may watch a doe run across a road attempting to avoid oncoming cars, but the presence of the doe is gone once the creature (hopefully) makes it to the other side safely. Now, the doe may still exist within our minds, but how long will we think of this insignificant creature before we move on with our day? Poetry and the written word give the reader a chance to relive this moment for eternity.

The line, “The power of preserving” reminds me of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55, in which the speaker addresses some lover of his, to whom which he states,

“Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone besmear’d with sluttish time.”

The speaker of the poem tells his lover that in writing a poem about her, she will live on for eternity in “this powerful rhyme.” The written word will preserve her memory far longer than “gilded monuments,” which will eventually deteriorate and are only in one location in the first place. Now, isn’t that far more romantic than just saying “I think you’re hot?”

Anyways, what can we take from Szymborska’s poem? I think we can take away the thought that writing gives a mere mortal the power to create something separate and different and perhaps otherwise impossible and put that something out into the world for all to see. Although some may argue with this, saying “You’re so stupid. How is it possible for a nonexistent doe that someone just wrote about become real? Are you on drugs?”

Well, no I am not. Although the doe may not be literally jumping off the paper and prancing around in the reader’s bedroom, the doe exists. It exists in our minds. Isn’t that enough?

Writers, like many other creators, are able to build ideas. And although these may be “just” ideas and not bicycles or tricycles or cars or steamboats or even rocket ships, don’t they all take us somewhere? What’s the point of your body travelling anywhere if your mind isn’t two steps ahead of it?

I love “The Joy of Writing.” Szymborska is the best. She always makes you think and brings up ideas you wouldn’t normally think of. Her latest book, “Here,” which was released last month is no exception. Feel free to check out the album I created based on her Nobel Prize winning poetry!

-Kevin

http://www.closerocean.com/

http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/CloserOcean