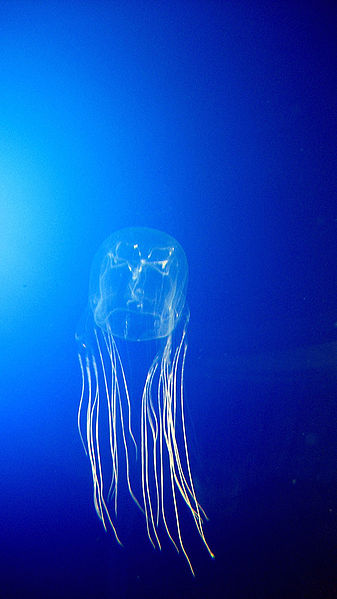

The waters of the Indo-Pacific are contain more lethally venomous organisms than elsewhere in the world. Some of these animals include the sea snake, the stone fish, the blue-ringed octopus, and the box jellyfish, also known as the sea wasp. Sea wasps, the world’s most venomous jelly, each have the potential to kill three adult humans (NOAA), and as a species it kills more people than sharks and crocodiles combined (web.utah.edu). These deaths are due to the particularly toxic substances that come from nematocytes lining the 3-m long tentacles of box jellies. Nematocytes, found in most species of jellyfish, are a type of cell that produces spiky structures called nematocysts, which, upon encountering an unsuspecting victim, become stuck and inject toxic substances. In box jellies, these substances cause skin cell death, respiratory arrest, breaking of red blood cells (“haemolysis”), and heart failure (Tibballs, 2006).

A few days ago, a ten-year-old girl was stung by a box jelly in Australia (check out the pictures from the article). Doctors seemed astounded that she survived, as the usual result from severe stings dealt by the sea wasp is death by acute respiratory failure or drowning, as victims are unable to make it back to shore before their hearts and lungs fail, or they are in such pain that they become unconscious while still in the water.

Finals week beats that, at least, right?

On a lighter note, a different sort of gelatinous sea creature is getting some press here at BU. John Finnerty, a professor in the Biology Department, has played a large role in developing the starlet anemone, Nematostella vectensis, as a model system for genetics and developmental biology. His work has in part shown that cnidarians (the scientific name for the group of animals containing jellyfish, sea anemones, corals, and a few others) have some more developmental genes in common with us than previously thought (Ryan et al, 2007; Finnerty et al, 2004).

Cnidarians are simple, brainless, nearly invisible creatures. Over 95% of their bodies are water; they have no organs in the sense that we do; and they don’t have much control over their motion. They eat and excrete through the same opening. They rely on their nematocysts to stun fish and crustaceous prey, in effect preventing their delicate tentacles from the harm of a thrashing organism, unless, of course, that organism is a human. However, most cnidarians are not in fact harmful to humans.

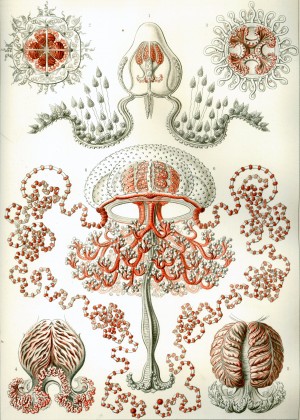

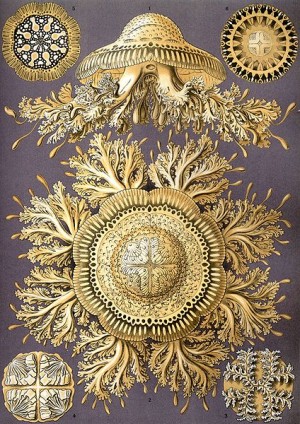

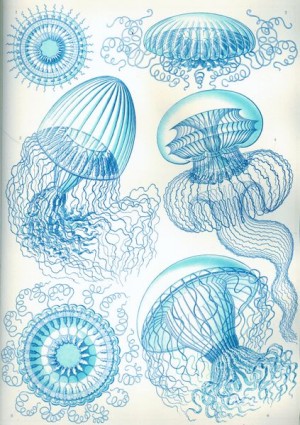

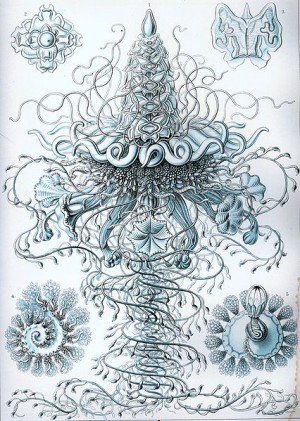

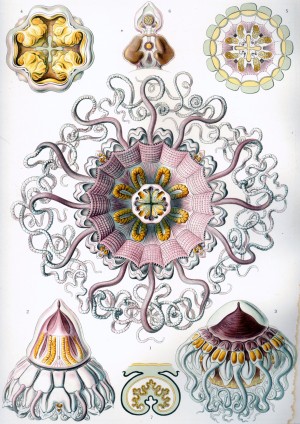

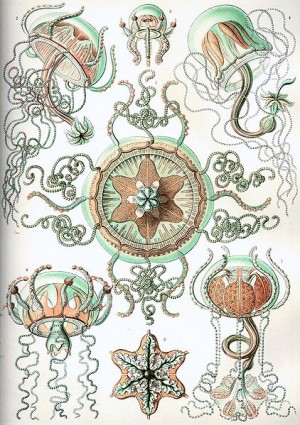

There are five types of cnidarians: corals and anemones, swimming jellyfish, stalked jellyfish, box jellyfish, and hydroids and siphonophores. Each one is beautiful in its own way, whether it be because of its elegant bell-like shape, its long, winding or fingerlike tentacles, or its hypnotizing waves of color (ctneophores are really nifty). To see all of the different shapes of cnidarians, check out this webpage. The aesthetic of the jellyfish is no new concept. The spiraling, floating, and sometimes danerous forms of jellyfish were depicted fancifully by Ernst Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of nature) back in 1904. Some of his plates are shown above. The shape of a jellyfish also makes for a very interesting paperweight.

There are five types of cnidarians: corals and anemones, swimming jellyfish, stalked jellyfish, box jellyfish, and hydroids and siphonophores. Each one is beautiful in its own way, whether it be because of its elegant bell-like shape, its long, winding or fingerlike tentacles, or its hypnotizing waves of color (ctneophores are really nifty). To see all of the different shapes of cnidarians, check out this webpage. The aesthetic of the jellyfish is no new concept. The spiraling, floating, and sometimes danerous forms of jellyfish were depicted fancifully by Ernst Haeckel in his Kunstformen der Natur (Artforms of nature) back in 1904. Some of his plates are shown above. The shape of a jellyfish also makes for a very interesting paperweight.

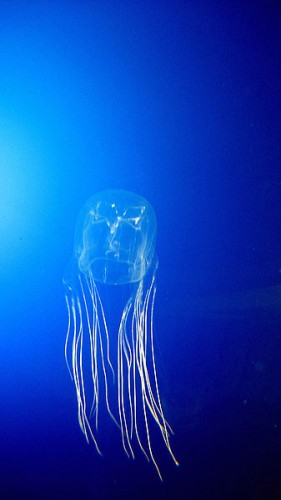

If you haven’t seen the Amazing Jellies exhibit at the New England Aquarium, you have certainly been missing out [click here for information on the exhibit]. There’s nothing quite like swarms of floating jellyfish in large cylindrical tanks filled with red or blue-lit water. Or, perhaps you’d prefer to look at baby jellyfish through a magnifying lens. In my opinion: seeing these jellies alone is worth the $20 entrance fee to the aquarium. While you’re there, it might be a good idea to check out the seahorses and seadragons too.

______________________

References

Finnerty, J.R., K. Pang, P. Burton, D. Paulson, and M.Q. Martindale. 2004. Origins of bilateral symmetry: Hox and Dpp expression in a sea anemone. Science 304: 1335-1337.

Introduction to Dive Medicine: Dangerous creatures of the sea. http://web.utah.edu/umed/students/clubs/international/presentations/dangers.html#BOX_JELLYFISH (Accessed Apr. 28 2010).

NOAA. NOAA urges all to respect and avoid unpleasant contact with marine creatures. Sept. 29, 2006. http://www.magazine.noaa.gov/stories/mag211.htm (Accessed Apr. 28, 2010).

Ryan, J.F., M.E. Mazza, K. Pang, D.Q. Matus, A.D. Baxevanis, M.Q. Martindale, and J.R. Finnerty. 2007. Pre-bilaterian origins of the Hox cluster and the Hox code: evidence from the sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis. PLoS One2(1):e153.

Tibballs, J. 2006. Australian venomous jellyfish, envenomation syndromes, toxins and therapy. Toxicon 48(7): 830-859.

One Comment on “Dangers and Beauties of the Sea”